Understanding Exposure: Aperture, Shutter Speed, and ISO

Proper exposure is the single most important feature of any photograph. It’s also the foundation of photography. You can be at the right place at the right time, but if you can’t properly expose the shot, you’ve got nothing. Today’s cameras do a pretty decent job of automatically selecting the proper exposure in most situations, but if you’ve spent any time shooting in the ‘auto’ mode, you know the camera rarely behaves exactly as you want it to. This article will teach you everything you need to know about exposure so that you can bend your camera to your will, making it do exactly what you want, when you want.

The first step in learning how to properly expose a shot is to learn what an exposure is, and how an exposure is made. Unfortunately, many looking to get into photography, and a surprising number of those who are producing very solid work, can be intimidated and confused when first learning about exposure due to the jargon photographers use to describe it. Luckily, exposure is an exceeding simple concept.

Exposure Defined

Put simply, “exposure†is the amount of light that you allow to hit the film or sensor. That’s it. The definition is right in the word itself: it’s simply the number of photons you expose the film to. You now understand what an exposure is!

We can make a very basic exposure by taking a light-tight box, putting a piece of film in it, and poking a hole in the box. This allows the photons streaming through that hole to strike the film, exposing it. How do we know when we have a “proper†exposure, one that makes the film react in a way that produces the image we want? That, of course, is the ultimate goal. Whether you’re using a box with a hole in it, or a modern camera, the principles outlined below apply just the same.

Controlling Exposure

We have three ways to control exposure: two of them, aperture and shutter speed, directly control how many photons will hit your sensor, and one of them, ISO, controls how sensitive your sensor is to those photons. We will start at the back of the camera, and work our way to the front, examining how we can control the exposure with each of these 3 tools.

ISO

Film comes in many speeds, some more sensitive to light than others. These different sensitivities, or speeds, were given arbitrary numbers to describe their sensitivity. A 25 ISO film is ‘slower’, or less sensitive, than a 100 ISO film, which is slower than a 6400 ISO film. Again, these numbers are entirely arbitrary, but each time you double the number, the film is twice (2 times) as sensitive to light. To expose an image on ISO 100 film you need twice as many photons to hit the film than you do if you use ISO 200 film, because the ISO 200 is twice as sensitive.  So, how do we control how many photons hit the film? Two ways:

Shutter Speed

Right in front of your sensor, or your film plane, is a shutter mechanism. There are a variety of ways to make a shutter, but no matter which mechanism your camera uses, the shutter stays closed until you trip the shutter button, at which point the shutter opens and the film or sensor is exposed to the incoming photons. Shutter speed is merely how long the shutter stays open.  This can be any length of time from days or hours to mere millionths of a second. The longer the shutter stays open, the more photons can pass through it. A 1 second exposure will allow twice as many photons to pass through the shutter than a ½ second exposure.

Aperture

An aperture is, by definition, an opening. If you’re using that wooden box, the aperture is the hole you’ve punched in it.  Your camera’s lens likely contains a variable aperture, which lets you adjust the size of this opening. In modern camera systems, the aperture is housed in the lens, in front of both the film and the shutter.

Because of the amazing way a lens works, by enlarging or restricting this opening, you aren’t changing how much of the image you see, or the field of view in photographer terms. Instead, you’re changing how many photons pass through the opening. If you’ve ever noticed someone’s pupils dilate, you already understand this. When it’s bright out, your pupils narrow to restrict how much light enters your eye, and when it’s dark out, your pupils dilate to allow more photons to enter your eye. A camera’s aperture works exactly the same way.

Aperture, like film speed, is also described by numbers, but not arbitrary ones. f/numbers or f/ stops, as they are called correspond to the amount of light allowed to pass through the aperture. An f/ number is literally the focal length (f) divided by the physical diameter of the aperture. So, a 100mm f/1 lens means that the aperture of that lens is capable of opening to 100mm in diameter. A 100mm f/2.8 lens means that the aperture of the lens is capable of opening to 36mm in diameter (100/2.8). As you can see, the larger the f/number, the more photons can physically pass through the aperture.

f/ numbers are traditionally marked off as follows: f/1, f/1.4, f/2, f/2.8, f/4, f/5.6, f/8, f/11, f/16, f/22, f/32, f/45, f/64. Unlike film speed, f/ numbers are not arbitrary, but are instead based on the innate physical properties of lenses. In order to cut the number of photons that pass through the lens in half, you reduce the aperture by a factor of √2, which is approximately 1.4. So, in any lens, setting the aperture to f/1 will transmit twice as many photons as f/1.4, four times as many photons as f/2, and eight times as many photons as f/2.8. Likewise, f/5.6 will transmit twice as many photons as f/8. So, when someone tells you to “Open up the lens one stop†they’re telling you to move your setting from, say, f/5.6 (if that’s the setting you were using) to f/4. Likewise, if someone tells you to stop-down, or close down the aperture one stop, you would move from f/5.6 to f/8.

Coming Together

We have three interconnected ways to affect exposure. Two of those deal with how many photons are allowed to pass through to the film or sensor, and one deals with how sensitive that film or sensor is. As you can now see, if you double the aperture and halve the shutter speed, or vice versa, you will allow the exact same number of photons to hit the sensor, and thus have the same exposure. An exposure of 1 second at f/5.6 allows the exact same number of photons to hit the sensor as an exposure of 2 seconds at f/8. Every one of the following combinations produces the exact same exposure:

- ½ second at f/4

- ¼ second at f/2.8

- 1/8 second at f/2

- 1/16 second at f/1.4

- 1/32 second at f/1

- 4 seconds at f/11

- 8 seconds at f/16

- 16 seconds at f/22

- 32 seconds at f/32.

We can throw ISO in and affect things even more. An exposure of ½ second at f/2.8 at 100 ISO will produce the same exposure as one made at 1 second at f/8 at 400 ISO. Here’s why: (1) doubling the shutter speed allows in twice as much light, (2) doubling the ISO twice makes the sensor four times as sensitive to the incoming photons. Combined, this means the exposure will be 3 stops brighter (one stop from doubling the length of the exposure and two stops from doubling the sensitivity of the film two times). To compensate, we close the aperture by 3 stops, going from f/2.8 to f/8.

This relationship is known as reciprocity, and as we will see in the next section, it is extremely useful.

Why?

You may be wondering why we need to have 3 independent ways to control the exposure of a given image. Why don’t we just use lenses with fixed apertures of f/2.8 or shutters with fixed speeds of 1/250th? This would certainly make cameras and lenses far cheaper to manufacture, after all. The answer requires a bit more explanation.

Aperture and Depth of Field

Depth of field (DOF) is the space in an image that contains acceptably sharp detail. We say acceptably sharp because, while a lens can only focus precisely at one single point, the transition from in focus to out of focus is not sharp and abrupt but gradual on each side of the precise focus point. A portrait of someone’s face where just the eyes are in focus and the rest is blurry has a shallow depth of field. A landscape shot that’s sharp from the foreground all the way to the horizon has a large depth of field.

Luckily, because of the unique property of lenses, we can control the depth of field. It turns out that when you use a larger aperture (ie a larger diameter opening, larger f/number, also called a “faster†aperture), you get a shallower DOF, meaning the space in the image that contains acceptably sharp detail is very small. As you “stop downâ€, or decrease the size of the aperture, DOF gets larger, meaning that more of the scene appears to be in focus.

Now we can see why we wouldn’t always want an f/2.8 lens. Portraits may look great with such shallow DOF, but sometimes we may want to shoot landscapes where the entire image appears to be in focus. Additionally, there is a cost and weight factor to consider. The larger the aperture, the more glass you need. After all, the larger the diameter of the opening, the more glass it takes to cover that opening, and optical glass is very expensive and heavy.

There are other benefits to using lenses with large apertures. As we know, a larger aperture lets more light through. Because of the way modern auto-focusing works, this means that your autofocus will be faster and more accurate. It also means that the image you see in the viewfinder will be brighter: modern cameras leave the aperture all the way open until you trip the shutter button, at which point it will stop down to whatever aperture you’ve selected and open the shutter.

Freeze!

Shutter speed also affects how sharp your final image will look, but not because of any property of the lens. The longer the shutter is left open, the more opportunity there is for either the camera or the subject to move. If the camera is locked down tight on a tripod and your subject is stationary, you can leave the shutter open as long as you want and your image will always be sharp. However, if you’re hand-holding your camera, the slight movement of your body can cause the camera to move during the exposure, which results in a blurry shot. Likewise, even if your camera is locked down on a tripod, if the subject itself is moving during the exposure you will still get a blurry shot. The faster the shutter speed, the less opportunity something has to move during the exposure, be it your hand or the subject. At 1/5000th of a second, even a racecar will appear to be frozen in time, because it simply doesn’t move very far in that time, but at 1/5th of a second, it will just appear to be a blur of color.

Noise

As you should now realize, photography is all about tradeoffs: larger apertures mean shorter exposures but also shallower depth of field; smaller apertures mean more depth of field, but require a longer exposure. ISO, alas, does not escape the tradeoff game. The more sensitive your film or sensor setting, the more noise will appear in the photograph. All films, even slow, super fine grain films like Fuji Velvia, exhibit a certain amount of noise, which looks like a uniform grain across the image. Films with a higher ISO rating, those that are more sensitive and require fewer photons to strike them to produce the same exposure, have bigger grain, and are described as “noisierâ€. Where a fine grained film like Velvia looks like it’s made out of extremely fine grains of sand, very high ISO films look like they’re made out of little clumps of sand. The effect of this noise is very evident in print: images shot at a higher ISO will be both noisier, grainier, and will also appear less sharp.

One of the many benefits of digital capture is the tremendous reduction in noise over film. The digital sensors of today are essentially noise free at lower ISO settings. The images don’t even look like they’re made out of fine grains of sand; they are so clean they don’t really have any grain at all. What’s more, files shot at ISO 400 on my new Canon 5d Mark II exhibit almost no difference, in terms of noise, from files shot at ISO 100, and things will only continue to get better. That said, at higher ISOs, digital files will exhibit quite a bit of noise, and this noise is generally uglier than film noise. Where film noise gets grainy, but uniform, digital noise gets patterned, and splotchy, and because the way our eyes and brains work, just looks uglier. Digital noise also tends to display color noise, which looks like random red, green, and blue splotches of color. You have undoubtedly seen these characteristics in low-light shots taken by low-end point-and-shoot cameras. Digital cameras already allow us to shoot in situations that were never before possible with film, and things will only get better, but the ISO tradeoff is still something that must be kept in mind.

Fin

You now understand the basics of exposure! There are a few more considerations to take into account if you’re truly want to master exposure, but understanding these basic concepts is essential if you ever want to realize the vision you’ve got in your mind.

Update

See part two of this article, Understanding Exposure, pt. Practice

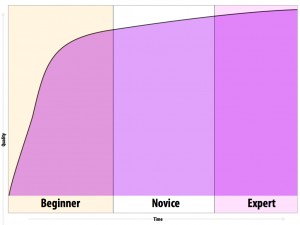

We’d be better off if we only became minimally competent at the things we don’t do that often or aren’t that important to us, and poured that extra time into our core skills, that next skill or project that will make you more valuable, or something you really enjoy.

We’d be better off if we only became minimally competent at the things we don’t do that often or aren’t that important to us, and poured that extra time into our core skills, that next skill or project that will make you more valuable, or something you really enjoy.